Table of Contents

Some links on posts are affiliate links and will earn us a commission from qualifying purchases

You can protect and strengthen your heart with a simple, low‑risk habit: walking regularly raises your fitness, helps lower blood pressure and cholesterol, and cuts the chance of heart problems over time. Bold that sentence: You can protect and strengthen your heart with a simple, low‑risk habit: walking regularly raises your fitness, helps lower blood pressure and cholesterol, and cuts the chance of heart problems over time.

Start small and practical – a brisk 30‑minute walk most days fits into many schedules and builds real heart benefits. Along the way you’ll learn how pace, duration, and simple supports like step goals or daily routes make walking both effective and easy to keep up.

Key Takeaways

- Short, regular walks improve heart function and lower cardiovascular risk.

- Brisk pace and consistent habit matter more than rare long walks.

- Simple tools and routines help you stick with walking for long‑term benefit.

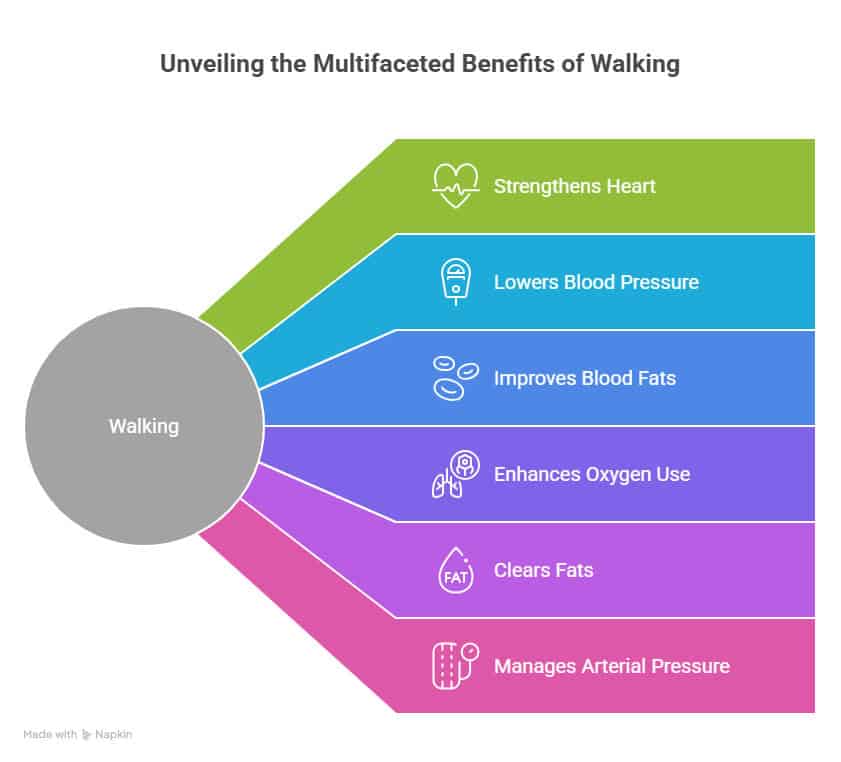

The Science Behind Walking and Cardiovascular Health

Walking strengthens your heart, lowers blood pressure, and improves blood fats through steady, repeated movement. Small changes in pace and duration change how your body uses oxygen, clears fats from the blood, and manages pressure in the arteries.

Key Mechanisms Linking Walking to Heart Function

Walking raises your heart rate to a moderate level. This increases cardiac output – the amount of blood your heart pumps each minute – so your heart muscle becomes stronger and more efficient. Over weeks, your resting heart rate often falls because each beat moves more blood.

Walking also improves endothelial function, the ability of blood vessels to widen. Better vessel function reduces strain on the heart and lowers the risk of plaque building up. Regular walking boosts mitochondrial function in muscle cells, helping muscles use oxygen and fat more effectively during activity.

Finally, walking reduces inflammation and insulin resistance. Lower inflammation helps prevent artery damage. Better insulin sensitivity helps control blood sugar, which links to lower cardiovascular risk.

Effects on Blood Pressure and Circulation

Brisk walking commonly lowers both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, especially if you already have mild hypertension. Each walking session causes temporary vasodilation (vessels widen), which reduces resistance to blood flow. Repeated sessions train vessels to stay more relaxed over time.

You also increase capillary density in working muscles. More capillaries mean better oxygen delivery and waste removal, easing pressure on the heart during daily tasks. Studies show moderate-intensity walking for 30 minutes most days produces measurable falls in diastolic blood pressure for many people.

If you have high blood pressure, start slowly and build to regular brisk walks. Even low-intensity walking helps, but moderate intensity gives stronger blood pressure benefits.

Impact on Cholesterol and Lipid Profiles

Walking changes your lipid profile in helpful ways. Regular brisk walking tends to raise HDL (the “good” cholesterol) and lower triglycerides. The effects on LDL (the “bad” cholesterol) are smaller but still positive when combined with weight loss.

Activity increases the enzymes that help clear triglyceride-rich particles from the blood. That lowers fasting triglyceride levels and reduces small, dense LDL particles that are most harmful to arteries. You also improve the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL, which is a useful risk marker.

Aim for consistent walking most days to shift your lipid profile. Combining walking with modest dietary changes gives larger drops in LDL and triglycerides while boosting HDL more reliably.

Evidence-Based Heart Benefits of Regular Walking

Regular walking improves heart health in measurable ways. It lowers your chance of heart attacks and strokes, helps control blood pressure, and improves how your body handles blood sugar and insulin.

Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease

Walking briskly for about 30 minutes most days links to a clear drop in heart disease risk. Studies estimate roughly a 15–25% lower chance of coronary events when you reach about 8 MET-hours per week (about 30 minutes a day, five days a week).

Faster walking pace often shows stronger benefits, partly because it reflects better fitness. Even modest increases in daily steps—moving from very low activity to 7,000–10,000 steps—cut your long-term risk of heart attack and stroke.

You also reduce mortality risk. Large observational studies find lower rates of cardiovascular death in walkers versus inactive people. The gains apply across ages and in people with existing heart disease or type 2 diabetes, so walking is useful for prevention and secondary care.

Lowered Hypertension and Improved Blood Pressure

Regular moderate-intensity walking lowers both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, especially if you already have mild hypertension. Programs that ask you to walk 20–60 minutes on most days produce small but meaningful drops in resting blood pressure.

Most benefits come from walking at least at a moderate intensity. However, even some low-intensity walking has lowered blood pressure in certain groups, like mild hypertensives, when done consistently.

To see change, aim to walk regularly and build up duration and pace slowly. Even a reduction of 5–10 mmHg in systolic pressure cuts your risk of stroke and heart disease substantially, so small blood pressure improvements from walking matter for your long-term heart risk.

Diabetes Prevention and Insulin Sensitivity

Walking helps control blood sugar and improves insulin sensitivity, lowering your risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Regular daily walking reduces fasting insulin and improves how your muscles use glucose, which in turn lowers cardiovascular risk linked to diabetes.

In people with diabetes, increasing walking volume associates with fewer cardiovascular events and lower mortality. Short bouts of walking after meals also blunt blood sugar spikes, making it a practical strategy for day-to-day glucose control.

Combine walking with small changes, like slightly brisker pace or extra minutes, to get better insulin response. These changes reduce your long-term risk of heart disease because improved insulin sensitivity lowers inflammation, blood lipid problems and other metabolic risks.

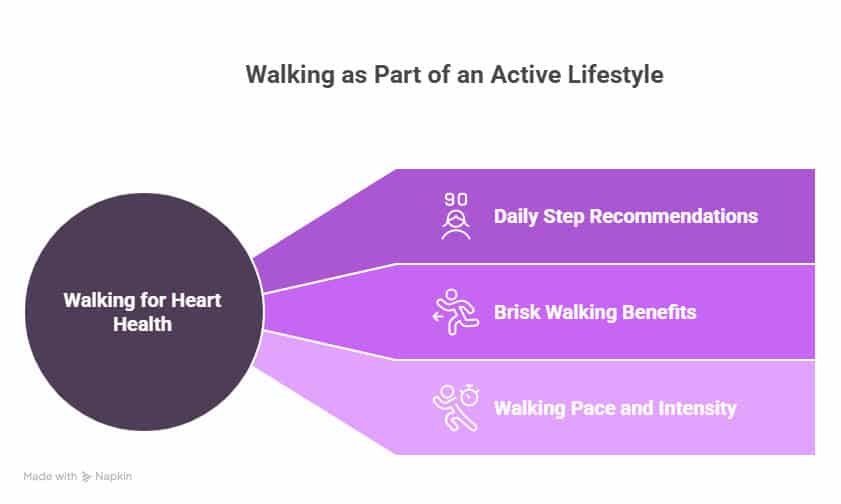

How Much and What Type of Walking Is Best?

Aiming for a steady step count and adding brisk pace sessions will give you the most heart benefit. Focus on realistic daily step targets, then increase intensity with brisk walking or short intervals to raise your heart rate.

Daily Step Recommendations and Guidelines

Most adults benefit from targeting at least 7,000 – 8,000 steps per day as a practical baseline for health. If you can, work towards 10,000 steps on many days; that often equals about 75 – 90 minutes of accumulated walking spread through the day.

Use a step-count device or phone to track your steps. Break goals into chunks: a 20 – 30 minute daily walk plus extra walking during errands or breaks usually helps you hit 7,000 – 10,000 steps. If you are currently very inactive, increase by 500 – 1,000 steps per day each week until you reach your goal.

Physical activity guidelines also recommend 150 minutes of moderate activity per week. You can meet that by brisk walking spread across several days while keeping a consistent step-count habit.

Brisk Walking Compared to Leisure Walking

Leisure walking is gentle and easier to sustain but gives smaller heart benefits than brisk walking. Brisk walking – where you breathe harder and can speak only a few words without pausing — improves cardiorespiratory fitness more quickly.

Aim for brisk walks of 20 – 30 minutes on most days or include several brisk 10-minute bouts across your daily walk. Combine leisure and brisk segments: warm up with a slow pace, increase to brisk for the middle portion, then cool down. That mix helps you raise your weekly intensity without overdoing it.

Brisk walking also raises calorie burn and helps lower blood pressure and cholesterol more than purely slow walking. Use step count plus perceived effort to measure progress rather than relying on pace alone.

Walking Pace and Intensity for Heart Health

Walking pace matters: moderate intensity generally means about 3–4 miles per hour for many people, while brisk walking sits at the upper end of moderate. You should notice a raised pulse and breathing, but still be able to speak short phrases.

If you prefer numbers, aim for roughly 100 steps per minute during brisk segments. Interval training — alternating 1–3 minutes brisk with 1–2 minutes easy – increases fitness and may fit into shorter daily walks. For long-term heart health, include at least 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly, using walking to meet those totals.

Adjust pace to your fitness and health conditions. If you have heart disease or other medical issues, get personalised advice before starting higher-intensity walking.

Walking as Part of an Active Lifestyle

Walking can fit into your day without special gear or a gym membership. Small changes to routines and travel choices help you build a steady walking habit that boosts heart health and daily fitness.

Incorporating Walking into Your Daily Routine

Make walking part of your day by adding short, regular walks that add up to at least 150 minutes a week. Start with a 10–15 minute brisk walk after meals, and aim for a pace that raises your breathing so you can still talk but not sing.

Use a pedometer or phone step counter to set clear goals, like adding 1,000 steps per day each week until you reach 7,000 – 10,000 steps. Schedule walks into your calendar as appointments.

Try walking meetings, walking while on phone calls, or parking 10 minutes away from destinations. These choices turn idle time into purposeful activity and help form a reliable walking routine.

Walking for Transport and Everyday Activity

Replace short car trips with walking to shops, stations, or work where possible. Even a 15–30 minute walk to public transport multiplies daily movement and makes active travel practical.

Plan routes that use pedestrian paths, safer crossings and green spaces. Combine walking with errands: do two or three stops on foot instead of a round trip by car.

If you commute by public transport, get off one stop earlier and walk the rest. These small changes build walking for transport into your life and make an active lifestyle easier to sustain.

Maximising Success: Supports, Motivation, and Environment

You can boost your walking habit by using the right places, tools and people. Choosing nearby green spaces, simple supports, and regular company makes walking easier to keep doing.

The Role of Parks and Nature in Heart-Healthy Walking

Parks give you flat paths, shade and fewer cars, so you can walk safely and at a steady pace. Look for routes with even surfaces and benches every 10–15 minutes so you can rest if needed. Green spaces lower stress and can help keep your heart rate steady during brisk walks.

Plan walks at times when parks are quiet to avoid crowding. Use a park loop of about 1–2 km for easy tracking, or combine loops to reach 30 minutes. Bring water, wear supportive shoes, and check park opening hours. If you live near a park, use it for short daily walks to hit a weekly goal without long travel.

Walking Groups and Social Support

Walking with others raises your chances of sticking with it. Join a local walking group or arrange to walk with a friend two or three times a week. Group schedules and accountability help you turn one-off walks into routine.

Choose a group that matches your pace and goals – social, brisk fitness, or gentle therapeutic walks. Use simple supports like pedometers or a shared app to set step goals and track progress together. If you can’t find a group, start one at a community centre or park noticeboard; even two regular walkers create reliable social pressure to keep going.

Special Considerations and Cardiac Rehabilitation

Walking can be a safe, effective part of recovery when you follow clear rules, monitor symptoms, and build time and intensity slowly. You will get the best results by combining walking with guidance from cardiac rehabilitation professionals and by adapting the plan to your current fitness and medical history.

Walking for People with Existing Heart Conditions

If you have had a heart attack, stent, bypass or have diagnosed heart disease, start walking only after your clinical team clears you. Cardiac rehabilitation programmes usually set the timing and initial intensity based on your procedure, tests and recovery.

Begin with short, frequent walks – 5–10 minutes, two to four times daily – and increase duration before speed. Use a simple exertion scale (e.g. Borg RPE 11–13) or a target heart rate range given by your clinician. Stop and seek help if you feel chest pain, severe breathlessness, faintness, or sudden dizziness.

Carry emergency contact information and any prescribed medicines. Wear comfortable shoes and dress for the weather. If you use a pacemaker or other device, check device-specific advice about arm movement and intensity. Report new or worsening symptoms to your rehabilitation team promptly.

Customising Walking Plans for Safety and Progress

Work with your cardiac rehab team to get a personalised plan that states goals, frequency, intensity, time and progression. A typical starting plan lists: frequency (most days), duration (start 10–20 minutes), intensity (light to moderate), and weekly progression (add 5–10 minutes or one extra walk every 1–2 weeks).

Use objective measures where possible: walking pace, steps per day, or clinician-prescribed heart-rate zones. Include warm-up and cool-down of 5–10 minutes, and add light resistance or balance work as advised. If medications affect heart rate, rely on perceived exertion and symptoms rather than heart rate alone.

Reassess every 4–6 weeks with your rehab team to adjust goals, manage risk factors and safely increase challenge. This structured approach keeps you safer, builds confidence, and supports long-term heart health.

Long-Term Effects: Walking and Longevity

Regular walking lowers your chances of dying early and helps you keep better health as you age. It improves blood pressure, blood sugar control, and heart fitness in ways that add up over years.

Evidence Linking Walking to Reduced Mortality Risk

Large studies show that brisk walking for about 30 minutes most days links to a lower risk of death from heart disease and other causes.

Risk reductions vary by study, but many report meaningful decreases in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality when people meet guideline-level walking.

Faster pace adds benefit. Walking briskly or at a moderate intensity often shows stronger mortality reductions than the same time spent at a slow pace.

You gain benefits even if you start later in life; people who increase walking after middle age still show lower death rates than those who remain inactive.

Aim for consistent volume and some brisk effort to get the clearest mortality advantage.

Lifelong Health and Quality of Life

Walking preserves function and mobility, so you stay independent longer and reduce risks that raise mortality, such as falls and hospital stays.

It helps control weight, lowers blood pressure and blood sugar, and reduces inflammation—each factor links directly to longer life expectancy.

Daily walking also supports mental health and sleep, which affect physical recovery and long-term health outcomes.

Simple habits – walking to shops, using stairs, and doing one or two brisk 20–30 minute walks most days – build a pattern that sustains longevity and lowers your overall risk of premature death.

Frequently Asked Questions

These answers focus on clear, practical effects walking has on heart health, blood pressure, cholesterol, and disease risk. They also give specific guidance on how long and how often you should walk, and how pace changes the benefits.

What are the primary benefits of walking for heart health?

Walking strengthens your heart muscle and improves circulation.

It raises your aerobic fitness, which lowers your risk of heart-related events over time.

Walking helps control weight and blood sugar, both of which reduce stress on your heart.

It can also improve mood and lower stress hormones that affect heart health.

How does regular walking affect blood pressure levels?

Regular walking can lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Studies show even moderate programmes – 20–60 minutes, a few times per week – produce small but meaningful drops in pressure.

You may see larger effects if you already have mild hypertension or follow a brisk routine.

Consistency matters: benefits increase when you keep walking over months.

Can walking reduce the risk of heart disease, and if so, how?

Yes. Walking reduces the chance of coronary heart disease and stroke by improving blood vessel function and lowering inflammation.

Epidemiological studies link about 30 minutes a day, most days, with measurable risk reduction.

Faster or longer walks give added benefit because they raise fitness and burn more calories.

Active travel, like walking to work, also contributes to lower long-term risk.

What is the recommended duration and frequency of walking for optimal cardiovascular benefits?

Aim for about 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity walking.

That equals roughly 30 minutes a day on five days each week.

You can break sessions into 10–15 minute bouts if needed.

For added benefits, increase to 300 minutes per week or add some higher-intensity sessions.

How does brisk walking differ from regular walking in terms of cardiac impact?

Brisk walking raises your heart rate more than a casual stroll and improves aerobic fitness faster.

It places greater training stimulus on the heart and lungs, which strengthens them over time.

Brisk pace is typically one where you can talk but not sing.

Vigorous walking brings even greater gains but needs to match your fitness and health status.

What role does walking play in managing cholesterol levels?

Walking can improve your lipid profile by raising HDL (good) cholesterol and helping lower LDL (bad) cholesterol and triglycerides.

Changes are modest but add up when combined with weight loss and healthy diet.

Higher volumes or brisk intensity tend to produce stronger improvements.

Regular walking also supports medications and other lifestyle changes that target cholesterol.

Recent Posts

The Science of Efficient Walking: Optimising Movement for Health and Speed

Walking is a natural activity most people do every day, but how efficiently you walk can make a big difference to your energy use and overall health. Efficient walking means using the least amount of...

When it comes to achieving our fitness goals, we all want to make sure we're getting the most out of our workouts. But how do we know if we're pushing ourselves hard enough? That's where heart rate...